I took some notes from the panel session this evening, which was the final event for the Vancouver portion of the Gairdner Symposium 50th Anniversary celebrations. Fortunately, they are in electronic format, so I could easily migrate them to the web. I also took notes from the other sessions, but only with my pen and paper, so if people are interested I can also transcribe some of those notes, or summarize them from the rest of the sessions, but I will only do that upon request.

As always, if there's something that doesn't make sense, it was my fault, not those of the panelists, and when in doubt, this version of the talk is probably wrong.

You'll also notice several changes in tenses in my notes - I apologize, but I don't think I'm going to fix them tonight.

Before you read the transcription below, I'd also like to comment that all of the speakers tonight were simply outstanding, and that I can't begin to do them justice. Mr. Sabine is simply an amazing orator, and he left me impressed with his ability to mesmerize the crowd and bring his stories to life in a way that I doubt any scientist could match. He was also an exemplary moderator. If the panelists were any less impressive in their ability to hold the crowd's attention, it was easily made up by their ability to give their opinions clearly and concisely, and they were always able to add insightful comments on each subject that they addressed. Clearly, I couldn't have asked for more from anyone involved.

There was also a rumour that the video version of the talk would be available on the web, somewhere. If that's the case, I highly suggest you watch it, instead of reading my "Coles notes" version. If you can't find it, this might tide you over till you do.

------------------------------------

Introduction by Michael Hayden

Michael Smith told reporters, on the day he won the Nobel Prize: He sleeps in the nude, has a low IQ and wears Berkenstocks.

Tonight's focus is different: DNA is “everywhere”.. it has become a cultural icon. Sequencing the human genome was estimated to take $3 billion and 10 years, and it took nearly that. Now, you can do it for about $1000. Who knows, it might even be your next Christmas gift. Personal genomics was the invention of the year in 2008.

Our questions for tonight – what are the advantages, and what harm can it do.

Moderator: Charles Sabine

Panellists:

Dr. Cynthia Kenyon,

Dr. Harold Varmus

Dr Muin Khoury

Questions: Personalized Genomics: Hope or Hype?

[Mr. Sabine began his talk, which included a slideshow with fantastic clips of Michael Smith, his experiences in the war, and was narrated with dramatic stories from conflicts in which he reported upon, and human tragedies he witnessed. I can't begin to do justice to this extremely eloquent and engaging dialogue, so I'll give a quick summary.]

Mr Sabine recently took a break from broadcasting to begin participating in science discussions, and to engage the community on issues that are tremendously important: science, genomics and medicine. His family recently found out that Mr. Sabine's father was suffering from Huntington's disease, which is a terrible hereditary genetic disease. With his father's diagnosis of Huntingtons, he himself had a 50% chance of developing the disease, as do all of his siblings. His older brother, a successful lawyer, has developed the disease, and is now struggling with the symptoms.

An interesting prediction is that in the near future, as much as 50% of the population will have dementia by the time they die.

From his experience in wars, if you take away dignity and hope, people will lose their moral compass. (Mr Sabine is much more eloquent than my notes make out, and this was the result of a long set of connected points, which I was unable to jot down.)

Huntington's disease is an interesting testing ground, for it's ability to predict personal medical futures. It has a high penetrance, and is one of the early genetic diseases for which a test was identified, thus, it is the precursor to the genetic testing and personalized medicine processes that people have envisioned for the future. But the question remains, will personalized medicine be a saviour, by enabling preventative medicine, or will it be a huge distraction by presenting us with information that just isn't actionable. Many people have different answers to this question: insurance companies would like to remove risk, and the personal impact is, of course, enormous.

Mr. Sabine recently took the test for Huntington's himself. The result was positive: he will suffer the same fate as his brother and his father.

[If only I could type fast enough! Fantastic metaphors, stories and wit.]

End of introduction – Beginning of the panel

Question: Is personal medicine a source of hope, or is it just hype?

Varmous: Middle of the road. First, The fact that we're talking about genes excites special attention – it's hereditary, and seem unchangeable. However, this new modality that plays a role in risk assessment is just one more part of the continuum of care we already have. All our environment and physical choices are just one more component of what goes into our medical care.

Second, We're already using medical diagnosis which is based on genomics. These are mostly high penetrance genes, however, so we have to consider the penetrance of each of the genes we're going to use clinically.

Third, it's not always easy to implement the changes in the clinic, when we find them in the lab. There is resistance – physicians are creatures of habit, there are licensing and cost issues. These things are important in how the future plays out.

Many of the new commercial ventures (genotyping companies) are grounded in a questionable area of science. There may be a slightly increased risk of a disease because of a couple changes in your genome, but it's not an accurate description of what we know. There are suppressors and other mitigating factors, so to put your health in the hands of a commercial vendor is premature.

Khoury: My job is to make sure that information is used to improve the public health. Have an interest in making sure that it gets used, and used well. Therefore, I'm for it, and believe it can be done. However, I have concerns about the way it's being used now. “The genie is out of the bottle, will we get our wish?” (Title of a recent publication he was involved in.)

Kenyon: Excited about it. Humans are not all the same as one another. Can we correlate attributes with genes? We know about disease genes. Is there a gene for perfect pitch? Happiness? Etc etc. It would be interesting to know, we could start asking if we had more sequences. What would you do with that knowledge? If you don't have the gene for happiness, how would you feel?

The more we know, the more we'll be able to do with the tests. We're too early for real action most of the time. Can you make the right judgements based on the information? Now, probably not, there's too much room to make bad choices.

Question: Is knowing a patient's gene sequence going to impact their care, and what role does the environment play in all of this?

Khoury: most diseases are interactions between environment and genes. Huntington's is one of the few exceptions with high penetrance. You need to understand both parts of the puzzle, to identify the risk of disease. It's still too early.

Varmous: Get away from phrase “sequencing whole genomes”, we're not there yet.. that would cost $100,000's. Right now we do more targeted (Arrays?) or we do shotgun (random?) sequencing. So we have a wide variety of techniques that are used, but we're not sequencing people's genomes.

In some cases there are very low environmental influences. Many people have gene mutations that guarantee you will get a disease.. These should be indicators where genes must be tested and knowing genetic information provides a protective preventative power.

Kenyon: Agree with Harry. Sometimes genes are the answer, other times we just don't know.

Khoury: There is a wide variety of diseases with a variety of possible intervention. Sometimes the diseases are treatable in environmental ways. (eg. phenylketonuria). However, single gene diseases make only 5% of the diseases that are affecting the population.

Genome profiles tell us that there are MANY complex diseases, and we can use non-genetic properties to indicate many of our risks, instead of using genome screens.

Varmous: The word environment does not include all things non-genetic. Behaviour is a huge component. Dietary, drug, motor accidents, warfare, smoking... they are controllable and make a huge contribution.

Khoury: Every disease is 100% environmental and 100% genetic. (-;

Question: given that a genome scan is ~$400-500, would you have your genome scanned. Would you share that information with anyone, and who would that be?

Kenyon: havn't had it done, would do it if there was a familial disease. She likes a little mystery in life, so probably wouldn't do it.

Varmous: Wouldn't do a scan – would only do a test for a single gene. The scan results aren't interpretable. The stats are population based, and not personal. He wouldn't publish his own.

Khoury: he's had the offer from 3 main companies.. and has turned it down. What you get from the scans is incomplete, but also misleading. Some people have had scans by multiple groups – they aren't always consistent. The information is based on published epidemiology studies.... and some of the replicable, some of them...well, aren't. The ones that do give stable information give VERY low odds risk. What do you do with the difference between a 10 and 12% lifetime risk? What changes should you make?

Why waste $400 on this, go spend it on a gym membership.

Kenyon: If you have the test done, it could mislead you to make changes that really hurt you in the long run.

Q: Should personal health care be incorporated into the health care system, and would it become a tiered system?

Khoury: We all agree that personal genomics isn't ready for prime time. After validation, and all....

(Varmous: define personal genomics), insurance companies are paying for this information, genetic counselling, and people make up their minds. The question is whole genome scans, though. And this is all about microarray chips and small variants. However, if the 3 billion bases are sequenced, what then? Would you start adding that information to do massive interpretation. We need to wait till things are actionable. Once that happens, we'll see them move through the health care system.

Will it become part of people's medical record.. probably not.

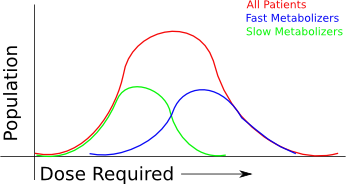

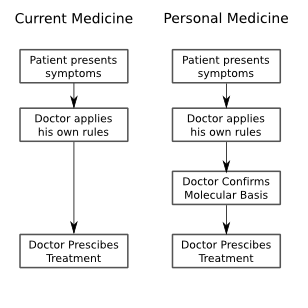

Varmous: The president is interested in using genetics in interesting ways. The most useful aspect is pharmacogenetics, and start looking at genetic variation and response to drugs. When you get sick away from your home, the physician you visit should have access to that information.

Kenyon: There are a lot of drugs already being tested that have very specific actions which only work for a subpopulation. Once we know what the variations in the population are that treatable with a drug, more drugs will make it through the trials.

Varmous: not a correction, just not sure the audience knows enough about cancers, which are heterogenous. Many of the changes are not somatic, and we don't yet have the tools to analyse cancers at that level.

Q: How worried should we be that personal genomics will lead to discrimination?

Khoury: it has been a huge topic for discussion. Congress has passed an act to prevent exactly that.

It's a good start in the right direction, and there's still plenty of room to worry.

Varmous: This is most worrisome in employment and insurance. There were few cases in the past anyhow, based on predisposition. However, some employers may discriminate against people who have diseases which may potentially reoccur, because they don't want their insurance premiums to rise.

The only way to avoid that is to have a Canada-like health care system.

Sabine: would you tell your employer?

Kenyon: it wouldn't be a problem at University of California, but it could be a major problem for people. There's a risk that things change and you don't know where it goes.

Sabine: would you trust insurance companies?

Kenyon: Gov't can't do things that harm too many people and stay in power. In long run, we can trust that things will be put right.

Khoury: not right now.

Varmous: I wouldn't reveal it [his own genome sequencing results].

Q: How do you suggest we bring personalized medicine to developing countries?

Khoury: Same technologies can be used everywhere around the world. The concerns around chronic diseases are there. They have their fair share of infectious diseases, and the genomic information will help with better medications, which will help on that front. We can also use the technology for solving other difficult problems, beyond human personal medicine.

Dr. Singer [the authority on the subject was pulled up from the audience]: It can help. There is a war being waged on the global poor, waged by diseases. Killing millions of people. We could use the technology to create better tests, better drugs, etc etc. We can use life-sciences and biotech to save people in the third world. Personalized genomics: that too could have an effect, but not at the individual level. If you apply personalized genomics at the population level... [I think he's talking about doing WGAS to study infectious diseases, and confusing it with personalized genomics.]

Varmous: Always eager to agree with Dr. Singer. The use of genetic technology could be very important for infectious diseases in the developing world .

Kenyon: Something about using WGAS to study..... [I missed the end of the thought.]

Q: How might this information [personal genomics] shape romantic relationships?

Khoury: Just a public health guy! But there's an angle: it's highly unlikely that we'll find the gene “for something”, so while he specializes in prevention and disease, personal genomics are just unlikely to be useful outside of that realm. He doesn't think it's going to have an impact, but there are medical applications such as tay-sachs screening. There are forms of screening, but it's not romantic in the sense of “romantic”

Varmous: We're unlikely to ever see genomes on facebook for romantic purposes, but some times it is useful in preventing disease. May be useful in screening embryos.

Kenyon: Thinks the same thing. Predicting love or even personality from DNA is impossible.. cheaper to do 2 minute dating. However, many of the screens are still useless in terms of predictions that really carry weight. We should instead teach statistics to kids to better understand risk. If we bring in testing, we have to bring in education.

Q: Should information be used to screen your potential partners?

Varmous: If he had genetic testing, and if he were single, he still wouldn't tell his dates.

Q: Genome canada's funding was reduced to zero. How do we advocate for funding?

Varmous: Wasn't aware of that change of funding. There are many factors to be considered. Both economic and political climates have to be considered. Scientists must keep explaining in an honest and straightforward manner how science works and it's contribution to the public. Do what you can, and engage the politicians! They do listen, and they learn – visit local pharma, etc etc. All scientists have to do their part.

Khoury: Harry said it all.

Kenyon: Opportunities arise all the time, engage everyone around you. Take the time to talk with people on the bus, whatever, but just in general seize opportunities, and they come up all the time.

Varmous: just don't become the crazy scientist on the bus who will talk to anybody.

Q: Epigentics are influenced by the environment, and we can influence them with our behaviour. How long will it be before we know enough about the epigenome before we can start making predictions about disease?

Khoury: The sequence variation we measure may mean something different for people, depending on the patterns we see. It can be a big factor, and the environment also complicates our efforts to understand how it all works together. Particularly in cancer. How long will it take to mature? Progress is moving forward rapidly, but can't make a prediction. Excited by prospects, though.

Varmous: Epigenomics is being most vigourously applied in oncology. Gene silencing and other effects can be seen in the epigenome. That may contribute to the cancer, and determine efficacy of drugs. However, the tools are still crude.

[Hey, what about FindPeaks!? :P]

Kenyon: Explanation of what epigenetics is.

Q: What kind of regulation should exist, if any, on the companies that do personal genomics.

Khoury: FDA does regulation, and the US oversight is fairly loose. Talk about CLIA. [previously mentioned in other talks on my blog, so I'm not taking notes on this.] Basically, more people are concerned, and people believe that other regulation is necessary.

Varmous: There's an uneven playing field out there. Certain things are tightly regulated, whereas other things are too loosely tested. Seems like DNA testing wasn't really the point of the original screening regulation, so that could be improved.

Sabine: Closing remarks. Thanks to everyone.

Labels: Talks